An open letter: In defence of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's right to tell the story of Rani Padmavati

A Bollywood follower and an ardent reader of Pinkvilla pens some thought-provoking points on the ongoing Padmavati controversy.

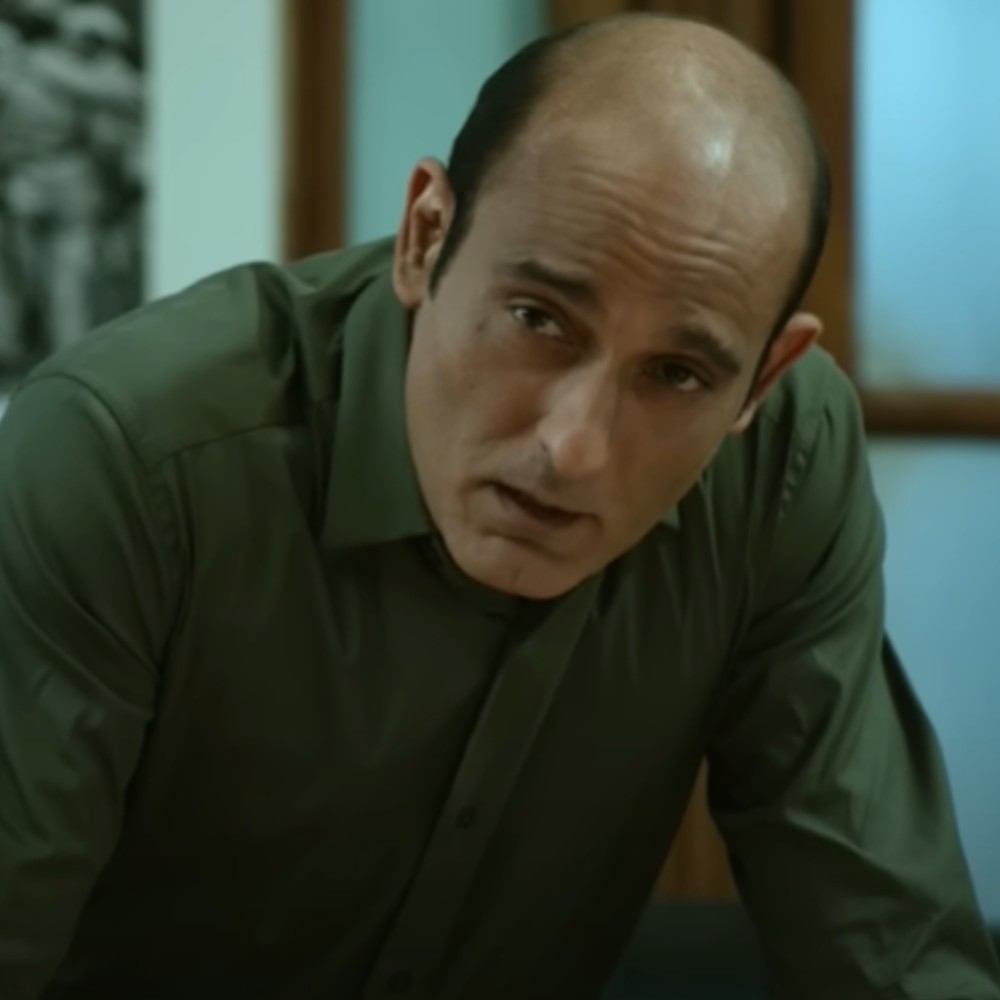

I was watching an assortment of videos on YouTube in bed this morning, and before I knew it, I was watching an episode of Rendezvous with Simi Garewal from 2002, where Sanjay Leela Bhansali, the man behind Khamoshi, Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam, Black, Saawariya, and Bajirao Mastani amongst other films, and his mother Leela Bhansali were being interviewed. It seemed that Devdas had just released, and Ms. Garewal, finding herself still being ‘haunted’ by it, had invited Mr. Bhansali to talk to him about it.

One of the first things Mr. Bhansali says in the interview is that he made Devdas thinking, during every minute of his making it, how the late Raj Kapoor would have made it. (And I now find myself immediately remembering his granddaughter, the actor Ms. Kareena Kapoor Khan saying ‘next’ when a reporter begins to ask a question about Mr. Bhansali’s latest film, Padmavati as she makes her way out a recent awards ceremony). Ms. Garewal, who has in fact worked with the late Mr. Kapoor, seems surprised by this admission, and begs to differ from him, and says that his vision, of the film and especially of the two women in it, was more romantic than it was erotic- which she says would have been the case had it been a Raj Kapoor film. And Mr. Bhansali sees the point in her argument and concedes that he infact saw his women as the images of the Goddess Durga herself.

The conversation then moves on to the conception of the film, and of the character of Devdas himself, and especially of his alcoholism, and his decline, and the troubled life of his own late father, the senior Mr. Bhansali, whose passing, Mr. Bhansali says, was the point that triggered the beginning of the film. As he carries on talking about his late father, of how he took solace in alcohol after having failed as a film producer, and therefore of becoming bitter, and anguished and violent, it dawned upon me why Devdas had struck a chord with me all those years ago, when I was wading through my own teenage, filled with dreams and anguish and disappointment, because of the vision of myself that I saw on the inside not matching the image that people saw of me, from the outside.

Devdas touched a chord in me because it was too beautiful to be true, and too operatic to be a slice of reality. Everything about of it was heightened, and every bit of its romance could have only been dreamt up by a man who had dreamt it all himself, all alone, within his own head. Devdas, it seems to me, was an attempt to understand life, and love, and beauty, and pain, by a man who at once understood it all too well, and didn’t really understand it at all. It was the work of a mind that saw life as a composition of notes strung together on a sheet of music, and played out in the pit.

Devdas, I felt as I carried on watching the interview, was the portrait in film by Mr. Bhansali of the hand that the senior Mr. Bhansali had extended to his long-suffering wife, from his deathbed, after more than two decades of subjecting her to a life in a tiny house, with two children, two dogs, and his own mother trapped in it, of making her fetch for them all, and of making her still having to be the best mother his children could have had. And it seems to me that Mr. Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s absolute love for and devotion to his mother is his armour to help protect his own spirit from becoming the offspring of his late father’s.

And I fear that we as a society are only all too readily pushing him in that very direction during the period of a year or so over which he has been making Padmavati, and especially over the last month. And I don’t believe that this society simply consists of those of us that think that his Padmavati is his attempt to demean a deified Hindu heroine, and therefore all of us proud Hindus, and those of us that therefore think that he deserves to be beheaded, and that he deserves to have his film never see the light of the day, or those of us in positions of power that wouldn’t speak for it because of our fear of losing it, or those of us in pursuit of power that wouldn’t do so due to our fear of losing out on a chance to achieve it. It consists of all of the above mentioned, and also of the rest of us who are standing by and watching the Kafka-esque horror show unfold right in front of us.

And I see that slowly but surely, just as night follows day, Padmavati, without any of us really noticing it happening, is slipping out of our collective consciousness. We are already looking for the next big story, the next scintillating scandal. And by so doing, I fear that we are only pushing its maker even deeper into his shell, even darker into his solitariness. He is after all, the man who says that the only pleasure in his early life came from hearing his mother sing as she went about doing her chores around their tiny home, and danced in moments of sheer abandonment. He conjures up love on the screen, because he seems too scarred by it to truly experience it again in reality.

And towards the end of the interview, Ms. Garewal asks Mr. Bhansali if he realises that his story could have gone a completely different direction; that his experiences could have made a delinquent out of him, seeped in delusion and self-pity. And it concludes as Ms. Garewal reminds him, and of us, of the power of a woman in shaping a child’s destiny. And that woman, at this moment, that has the power to make or break the life of this sensitive, complex, fragile and all too human son appears to not be Ms. Leela Bhansali, as it was back then, but Rani Padmavati herself.

The Rani, it appears, has had a life- even if some of us were to think it a mythical one- that has long completed its relationship with the world. Maybe it is the turn of those that want to tell her tale, amongst other tales of various degrees of truth and imagination, of motivation, of intent and vision and capacity to carry out and fulfill theirs? And maybe, just maybe, the man that has even taken his mother’s name as a part of his own, would know a thing or two about imbuing his Padmavati with the dignity that she deserves? And maybe, just maybe, a. Sanjay Leela Bhansali, is as much an Indian spirit that is deserving of our attempts at protecting it and defending it and enabling it to have its dignity as is the spirit of Rani Padmini? For the latter, though she may have been a Goddess, is long dead whereas the former, though all too human, is still alive, amongst us. And maybe, in trying to preserve the name of a heroine of the past, we are stifling the voice and mind of someone just like us?

Disclaimer: Views and comments shared in this post are strictly entitled to the author. We do not provide any opinion, conclusion or any assurance on them.

JOIN OUR WHATSAPP CHANNEL

JOIN OUR WHATSAPP CHANNEL