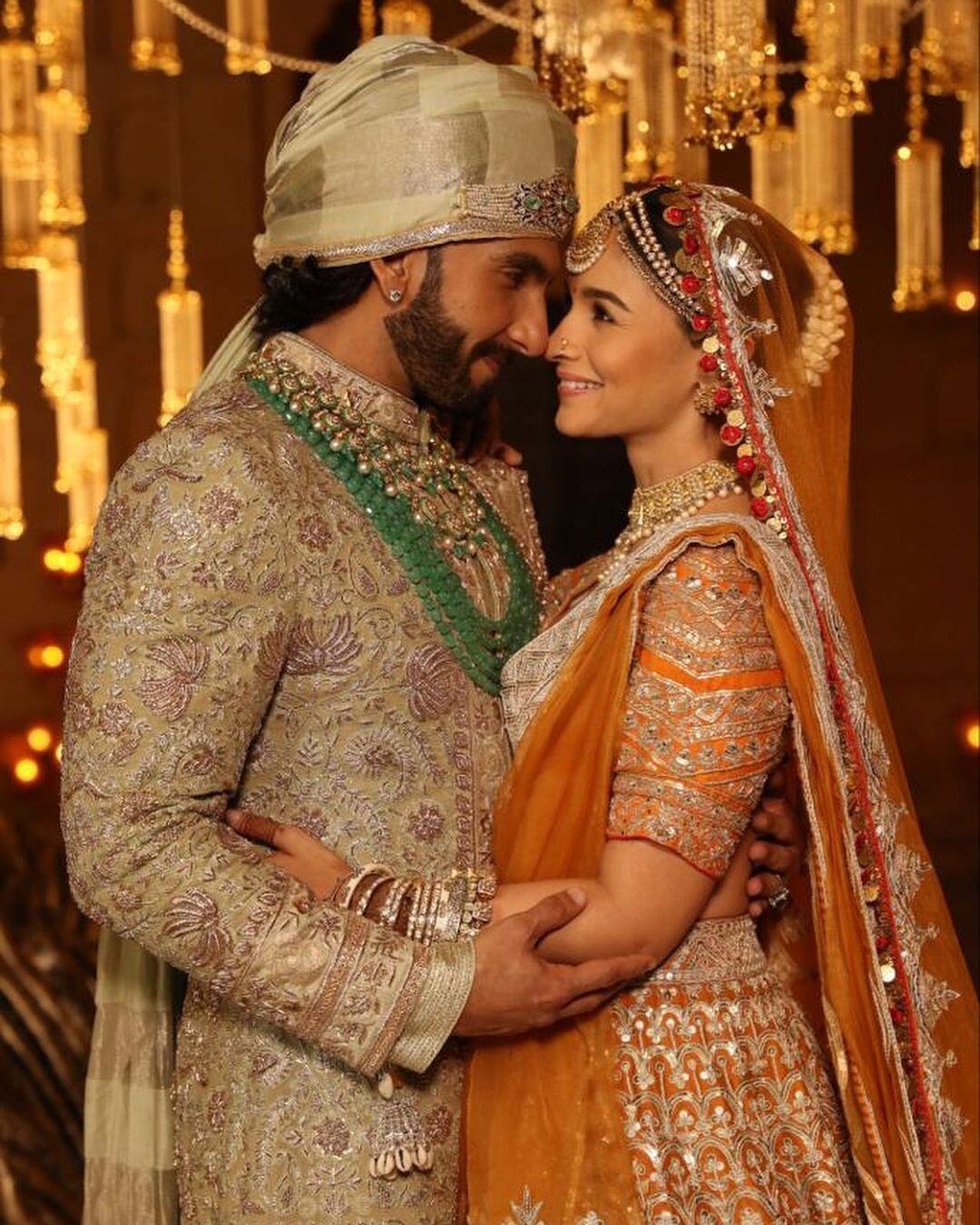

An article on how Bollywood is perceived in the west

I came across this rather interesting article in Live Mint by the British movie critic and historian Derek Malcolm.

It talks about how Bollywood is perceived in the West. At the end of the day we are still perceived as all song and dance.

Give it a read and share your thoughts. Its a rather long article, but I have some excerpts here. Please read the original article to get the context.

It was, however, a pity that Bollywood: The Greatest Love Story Ever Told, produced by Shekhar Kapur but put together by others, didn’t do what was expected of it. Here surely was a chance to show that Bollywood (and I know the very name jars with some) has a unique history of fine films from master directors such as Guru Dutt, Bimal Roy, V. Shantaram and Mehboob Khan, who were not simply concerned with clichéd stories and ever sillier song and dance numbers, but often made films of social and cultural significance.

Indian cinema is indeed Bollywood, and nothing much else. And that means song, dance and star personas emitting romantic clichés. They’ve heard about the movies but they don’t actually go to see them

Our view of Bollywood, however, is not one bought from experience. We don’t actually go to the Bollywood movies that often make so healthy a profit in our multiplexes. It’s the Indian immigrants who do, particularly the older generation, largely to be reminded of home. Their sons and daughters tend increasingly to prefer Hollywood, which provides better car chases and more luxurious special effects.

The real influence of Bollywood on anyone other than the diaspora is practically nil. It’s thought to be a bit of a joke—a huge engine that spews out dozens upon dozens of films a year, some of which make large profits but most of which sink without a trace. A couple of years ago, the main companies distributing Bollywood in the UK organized press shows for British critics. They duly went along to the first two or three. But the reviews were short and often negative, and soon the idea of adding to the 10 or 12 new films opening in London each week with a slice of Bollywood was quietly dropped.

I’m constantly told that there are now a number of young film-makers determined to alter this situation, and I met some of them at Cannes. I was shocked to find that a couple of the youngest had only seen a few Satyajit Ray films and had never heard of Adoor Gopalakrishnan, generally considered the best director of non-Bollywood films in India just now. I was also surprised that few of these possible saviours of Indian cinema had not gone to see many of the films at Cannes which would have given them a few ideas as to how to change things.

I wish them luck. If you don’t want to make an overtly commercial film, it is a very hard row to hoe in India just now. But let’s have a little judicious doubt about the claims made for Bollywood itself. Despite the huge success of Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire in the West if not in India (which was a better directed Bollywood film in all but ownership), Bollywood is not the flavour of the times. It may like to think it is, but that’s largely a hopeful myth.

JOIN OUR WHATSAPP CHANNEL

JOIN OUR WHATSAPP CHANNEL